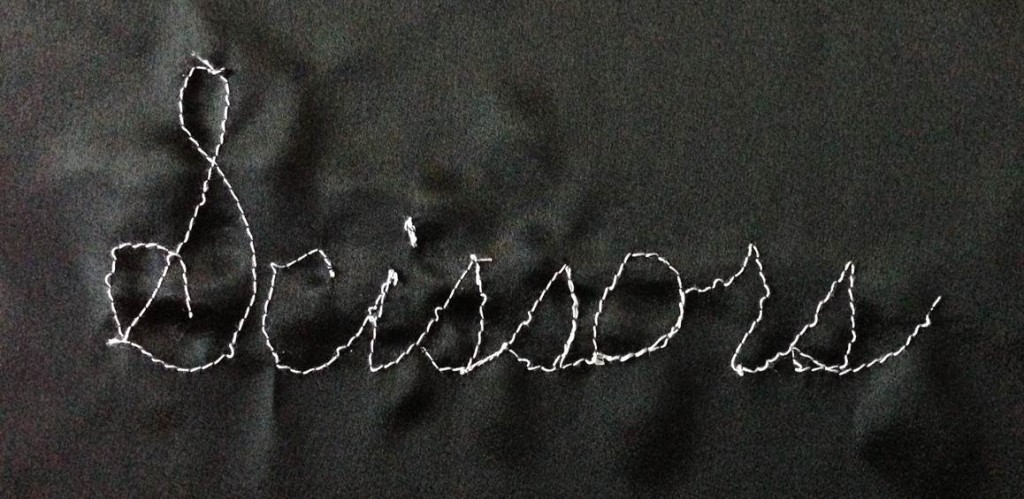

The earliest known scissors appeared in Mesopotamia about 3,000 to 4,000 years ago. The first scissors trademark was granted in 1791. (And for those who love the word scissors: I believe it’s a plural noun used with a plural verb.)

In an obscure corner of Jersey when my first tool—a pair of scissors—was placed in my hand, the cool, stainless steel bit my flesh and the sharp edges of the blades stood still in my palm as my grandmother warned me of danger.

The weight of the scissors turned heavy and the glint of silver reflected my mirror image as I raised the scissors to my face and peered into my eyes. The scissors shined like everything my grandmother used, that utilitarian shine she gave to things she needed to survive.

Grandma Janet took my fingers and slipped my thumb though the smaller hole, my last three fingers through the larger hole, wrapped my index finger under the larger handle, and covered my hand with her calloused hand in a tight grip. She smelled of eucalyptus and tomatoes.

Together we opened the blades. I watched two blades intersect and chop a red thread in half. The scissors let out a violent sound. The red cut thread fell to the floor. My fingers and the two blades seemed like two swords slicing thread that Grandma Janet usually cut with her Hungarian teeth.

Even at age seven, I had a sensitivity for line. I spent the first day with my scissors cutting lines. Straight lines. Lines that divided things in two. One side equaled the other half. At age thirteen, I used the same scissors to cut the bullshit. To find the truth hidden inside. At age sixteen, I learned to cut circles, to curve the scissors like the waves of an ocean, to tear and stretch and abandon the anchor of the straight cut for a more uneven feathered cut that kept the magic of the fringe of the fray.

Those around me were given other tools, but I was the only girl given a pair of stainless-steel scissors, not purple childproof-plastic scissors because my grandmother, who sewed for a living, believed in the molecular strength of American steel.

“Keep them close to you,” my grandmother said. “They’re a weapon.”

“You could stab someone in the back,” she said.

“Or like me you can make another woman a wardrobe of beauty.”

At night I slept with the scissors under my pillow and I dreamed of a life of comfort in the impossible nature of life’s cutting edge.

I brought the scissors to college at age 17, where I found myself shaping scissors out of clay when asked to sculpt an object. I remember the pure joy when my thin clay-scissors survived the fire of the kiln and the teacher and the other students holding my scissor-art in their hands, praising me for capturing the “reality” of a tool as if they wanted to cut something in half. And I remember returning the next day to retrieve my ceramics and tools—and my clay scissors were broken in two and the stainless-steel scissors my grandmother had given me were stolen.